Reusing Industrial Buildings in an Urban Core

By Alyssa Koehn

Date

August 4, 2017Industrial buildings are often designed with a focus on their purpose rather than their aesthetics and while some are beautiful, they can also be unsightly. They often sit empty once abandoned by their intended industry because their specific designs make them challenging to reuse or repurpose. When industrial areas are located adjacent to an urbanizing downtown core, how can we maintain their industrial character while taking advantage of this valuable land area?

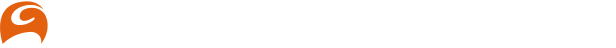

Minneapolis, Minnesota is a city that is faced with this challenge and exploring creative solutions. With a history in flour and beer production along the Mississippi waterfront, what is now the urban core, is still home to multiple industrial scale breweries and tall concrete grain silos. Many of these buildings were torn down or sat abandoned once flour production began to decline in the early 20th century. But as the city urbanized and the downtown core grew into an urban space, finding a use for these buildings became imperative. The city’s solution was to maintain the exteriors and historic signage, and thus the traditional industrial character of the city, while adapting them into creative housing and office properties.

This was not a simple design exercise, given the unique design of the original structures. One example is the transformation of the Schmidt Brewery into affordable artist lofts. The architect from BKV Group spoke of the challenges of this project to Curbed:

“Each building had different floor heights from the next,” Krych says. “So it was a huge challenge to make this accessible and figure out how to connect all of this to the one singular building from another. … We tried to be respectful that these were residences where people live, so we didn’t get carried away with trying to save everything,”

Another creative example is the Mill City Museum by Thomas Meyer constructed within the burnt-out ruins of the historic Washburn A mill. The project team preserved the crumbling exterior wall of the original mill that formed a new “courtyard”. Inside the shell of the original building they constructed a sleek glass office space, thus juxtaposing old and new. The building primarily contains a museum that celebrates the history of the city and the site. While the mills may no longer be operational, their history lives on through this space.

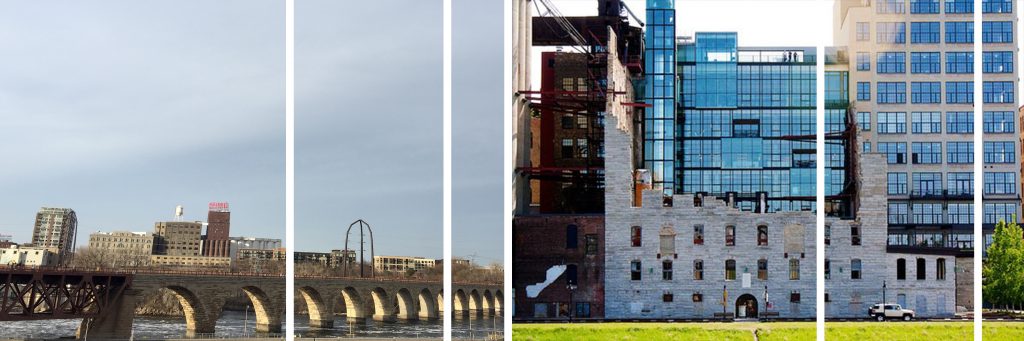

Another city embracing urban industrial transformation is Toronto’s pedestrian-oriented Distillery District. Toronto’s Gooderham & Worts Distillery was the largest in the world and is a designated Canadian historic site due to its Victorian industrial design. In the early 2000s, the 47 buildings comprising the distillery began to be renewed by developers. Their stated goal was “to combine the romance and relaxing atmosphere of European walking and patio districts with the hip, cool dynamic of an area like New York City’s SoHo or Chelsea.” The District is now a walkable, vibrant urban space on the outskirts of the downtown core.

Most of these projects have fully eliminated their industrial use during their transformation. This poses another question – can we maintain industry while adding density and other uses to the neighbourhood? Modern industrial zoning is often rare and pushed to the outskirts of the city. Are there ways to take advantage of these traditional industrial sites to integrate low-impact industry back into the city? This is something San Francisco is currently exploring with it’s PDR (Production, Distribution, Repair) zoning.

Additionally, many adaptive reuse projects save only traditional brick-and-stone type industrial buildings. What about more modern forms of industrial architecture- such as the mid-century buildings in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood (shown in the pictures above, courtesy of the Vancouver Archives)? In these neighborhoods, is it about maintaining industrial character through the buildings themselves or engaging history by continuing to provide a space for industry?