Is Public Space Political Space?

By TH!NK by IBI

Date

November 6, 2017What’s the role of protest in plaza design? How do you consider potential political uses when designing a public space? Whether explicitly stated in their entries or not, these were the questions considered by the architects redesigning a MUNI station and public plaza in San Francisco’s Castro district. The redesign of Harvey Milk plaza was inherently tied to protest, as was explained in the description of the design competition:

“In 1985, the plaza area was named in honour of the civil rights activist and elected official Harvey Milk, who lived and worked on Castro Street before he and then-Mayor George Moscone were both assassinated in 1978. Harvey led soapbox political rallies at the plaza which has since been used as a gathering place for community protests and celebrations.”

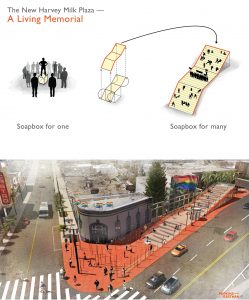

The winning design, by Perkins Eastman, very intentionally wrote this history into their design, building on the legacy of this public space as a place for both rallies and vigils. Their tiered plaza creates a permanent “soapbox” space that both looks out to and is viewed by the city, and their incorporation of “candle” lights across the plaza visually ties the space to the many vigils that have been held there. While this design is likely to change significantly before any sort of construction moves forward (as there is already vocal public concern with moving the entrance to the transit station to the distant, uphill portion of the site), the reason this entry was chosen is the way it integrates the public with the political.

The winning design for Harvey Milk Plaza, by Perkins Eastman. (Image Credit: Perkins Eastman) Click here for larger image.

Protests have sharply and steadily increased over the past few years. In Washington, even prior to the turbulent election in 2016, protests of all sizes, as tracked by the Metropolitan Police Department, have been climbing in numbers since 2014. The public realm is traditionally a space for engaging in democracy. What are the best practices for designing public spaces with the political in mind? How can plaza design affect the success and safety of a public protest?