Raising The City Makers of Tomorrow

“If children are not designed into our cities, they are designed out” says George Monbiot, in an interview with Curbed. Although children make up more than a quarter of the global population, they’re often muted from conversations about their environment.

Organizations like the Bernard van Leer Foundation advocate for the importance of city-making at the scale of 95cm- the average height of a 3 year old. This approach calls for children to be considered in city making practices and emphasizes the value in allowing children to participate as well.

North America has historically dismissed children from contributing to “adult” discussions regarding politics and education, even though children are sometimes the very issue being discussed. The recently launched Facebook Messenger for Kids is a prime example of the contentious case for children’s right to participate. Child advocacy groups have expressed their concerns about the app, saying that children are ‘too young for social media’. But as social media becomes an increasingly significant means by which we communicate with one another, then why shouldn’t children be able to join the platform as well? Instagram, YouTube and Snapchat have already grown to be staples of childhood and teen communication, and kids now even play a role as influencers, helping the industry decide where to go next.

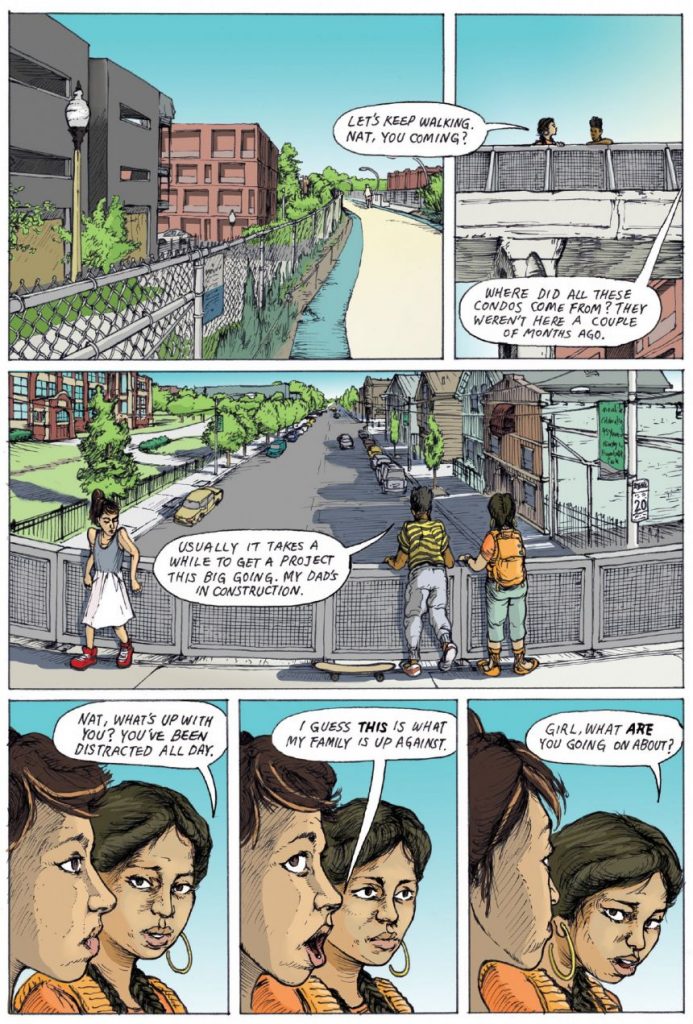

An excerpt from No Small Plans, an urban planning graphic novel published by the Chicago Architecture Foundation. Click here to view larger image.

While the world may not be intentionally designed for children, children participate in the world either way. Masters of imagination, transformers of puddles into the Great Barrier Reef- shouldn’t we be harnessing this creativity rather than neglecting it?

As creative industries become increasingly digitized, children have been given more agency to learn new technologies as well. Games like Minecraft bridge the gap between play and education and may even be helping raise the next generation of designers.

For children belonging to minority groups, these tools are particularly important as minority groups are vastly underrepresented in architecture and STEM industries. Although the last few years have seen improvements, the architecture industry is unarguably lacking in diversity. The industry places lofty financial barriers on aspiring architects as well, requiring high levels of financial investment and extensive education in order to reach accreditation. As it stands, African Americans account for only 3% of architects in the United States.

Michael Ford, AIA Associate and Founder of Hip-Hop Architecture Camp uses hip-hop as a means of introducing marginalized youth to architecture, urban planning, and design in a medium that meets them on their terms. “Hip-hop lyrics give an unfiltered depiction of urban planning and architecture” says Ford, noting that even when architecture is discussed in the classroom it’s mostly lavish Greek and Roman examples that are shown rather than those that speak to present minority groups. If children can’t see a place for themselves in their own environment, it’s easy to feel disenfranchised from participating. Hip-Hop Architecture explores the lyrical portrayals of urban life that have been left out of urban planning books. The program also helps kids write their own architecture-minded hip-hop songs, enabling them to find agency in their world. Kids also learn how to use the 3D-modelling tool, Tinkercad to create new environments of their own. Hip-Hop Architecture Camp runs 4-day sessions across North America throughout the year with hopes to increase minority involvement in architecture.

In Chicago, the Chicago Architecture Foundation recently published a graphic novel to teach children about urban planning and design. Titled No Small Plans, the book was inspired by Daniel Burnham’s famous 1909 Plan of Chicago and follows a diverse neighborhood group around the city in past, present, and future times. No Small Plans does not shy away from the messiness of planning issues as well and teaches its readers about racial and class discrimination, gentrification, eviction, and segregation- giving the characters a voice to stand up for injustices. The book was funded through a crowdfunding campaign that raised three times the amount of their $20,000 goal. For every $25 donation, funders received a book for themselves and another was donated to a Chicago student. Over 5000 copies were distributed to students last year.

The CAF also created a ‘reader’ program to help teachers educate their students on the issues of urban planning on architecture. The guide can be found online for free, where it links to other useful resources such as and Urban Planning Vocabulary Guide and Metropolis: A Green City of Your Own– an urban planning lesson plan for students in 3rd-5th grade.

Images from No Small Plans, published by the Chicago Architecture Foundation.