London Architecture: Dynamic, Historic, Diverse

By Jenny Dunphy

Date

February 1, 2017Architecture is communication with the past; memories of London’s previous lives are etched in its buildings and masterplan. The mysterious depths of London’s landscape are a consequence of centuries of human needs. London actually consists of two cites, the City of London and the City of Westminster. The remainder of London, as recognised now, consists of a further 32 boroughs, many of which previously existed as villages that have now been absorbed as London grew into a single city. The length of time that area has been inhabited is reflected within the architecture of the city.

London’s architecture connects you with the past, each era displaying its own vocabulary and sense of values. The City of London first came to prominence when it was inhabited by the Romans following the Roman Conquest in AD 43, though it was based on an even earlier occupation. It was originally established as a trading post, a function which continues to this day. This occupation has led to the remarkable juxtaposition of the most technically advance buildings next to archaeological remains from the Roman occupation.

Tower Of London – White Tower March 2006 by David Iliff is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0, from flickr.com

Located at the eastern edge of The City, The Tower of London exhibits the medieval approach of brutal functionality. The White Tower (1078) stands much as it did in the Middle Ages; with its primary function as a fortress, its simple form functions well as a stronghold. It’s presence at a key access point across the Thames gave it strength, and its stature was a deterrent to attack. Now, its role is purely ceremonial, though it still famously houses the crown jewels and has a cultural significance. This was highlighted by its central role in the art installation ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ by Paul Cummins and Tom Piper, which formed part of the remembrance day commemorations in 2014 and marked one hundred years since Britain’s involvement in the First World War.

The Tower, in addition to its more common perception, was – and still is – a royal palace. Notably, the growth of London can be traced through its palaces. The city has retained the 16th century display of power that is Hampton Court Palace, which was initially far more modest. It was redeveloped by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in 1529 and later given to Henry VIII in an act of appeasement. It represents two distinct styles, Tudor and Baroque, based on Italian renaissance influences with pink decorative brickwork and stylised chimneys. Later, Sir Christopher Wren drew up plans for its modernisation in response to Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles.

16_58_Hampton_Court_Palace__-_panoramio by Brian Gillman, 2011, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0, from Panoramio

Sir Christopher Wren continued his influence on the development of London. The melodrama of 17th century expression is personified in his rebuilding of St. Pauls Cathedral, which was completed in 1711.The striking large dome is a symbol of the London skyline with an equally impressive façade similar to the baroque style of 17th century Rome. At the same time that Wren was working on St. Paul’s, he also submitted his plans for the rebuilding of London following the Great Fire in 1666. This was one of the few attempts to shape London using a cohesive masterplan, but was never adopted.

St Paul’s Cathedral, London, England – Jan_2010 by David Iliff, 2007, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Copyright by GNU Free Documentation Licence version 1.2, from Wikimedia Commons

The Cathedral survived direct hits during the blitz and has born witness to many historical changes in the last few hundred years, adding to its presence on London’s skyline. It continues to have a significant influence on the development of London today, with views of the cathedral protected from a variety of points around London. Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners’ Leadenhall Building is canted at a 10 degree angle to maintain clear views of St Paul’s along Leadenhall Street. As a further indication of the influence Wren had on the development of London, his epitaph in St. Paul’s reads ‘If you seek his monument – look around you’.

The Leadenhall Building by Laurie Nevay, 2016, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0 Generic, from Wikimedia Commons

By 1811, London was the first city to hit one million inhabitants, and remained the world’s largest city until 1957. The Victorian Industrial Revolution propelled a new wave of buildings into the London landscape. With new methods to mass produce glass, the material language changed considerably. The Crystal Palace, built in 1851 from cast iron and glass, held the Great Exhibitions of 1851 and displayed the innovative style and techniques available. It was designed by Joseph Paxton and was originally built in Hyde Park, then relocated to South London due to its popularity, where the area was renamed Crystal Palace. Although the palace no longer exists, having burnt down in 1936, it opened the minds of architects and designers to the possibilities of the new materials and construction methods.

Beyond manufacturing revolutions and royals, the city has been shaped by a range of notable events, including numerous invasions, starting with the Romans. Other significant tragedies such as The Great Fire of London and two World Wars had a great influence on the development of the city but, due to the level of destruction, allowed for reinvention and improvement. With each rebuild, the city advanced and with each invasion came new diversity. From post-war migrants to pre-16th century invaders, new entrants to the city brought inspiration from across the globe, enlightening the city. In the late 1920s, the city benefited from an influential group of architects settling in London from across Europe. New ideas were debated to solve the housing problems brought by over population.

Crystal Palace from the northeast from Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851-1854 by Dickinson Brothers, 1852, and is in the public domain

More recently, the 2012 Olympics were seen as an opportunity to regenerate large parts of London. More than just temporary sports venues, the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is a new cultural district. Each event venue has been adapted for continued use. Zaha Hadid’s aquatics centre has lost its somewhat ungainly wings. Hopkins’s velodrome has been retained. And the stadium designed by Populous, is now home to West Ham United football club, following extensive reconfiguration. The athletes’ accommodation, East Village, has been converted to housing, bars and restaurants. This lasting legacy of the Games has rippled through the area and the city, notably in the improvement of infrastructure.

An integral part of the city’s architectural language is its transport. The River Thames has been vital to London’s identity and its relationship to the environment. Ease of transport was the reason why the Romans chose London – it’s the best location for the Thames to be bridged in the first place. The many bridges of the city tell their own architectural story from original London Bridge and the more recognisable Tower Bridge, built in 1894, to the recent Millennium Bridge, built in 2000 by Foster + Partners, in conjunction with Arup, and the pedestrian additions to Hungerford Bridge by Lifschutz Davidson. Perhaps the best combination of both river and transport is in Pascall+Watson’s re-designed Blackfriars Station, which dramatically spans the river and provides a beautiful distraction while waiting for a train.

St_Pauls_Cathedral_and_Millennium_Bridge by Alexandre Buisse, 2007, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 Unreported and BY SA 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic, 1.0 Generic. Copyright by GNU Free Documentation Licence version 1.2, from Wikimedia Commons

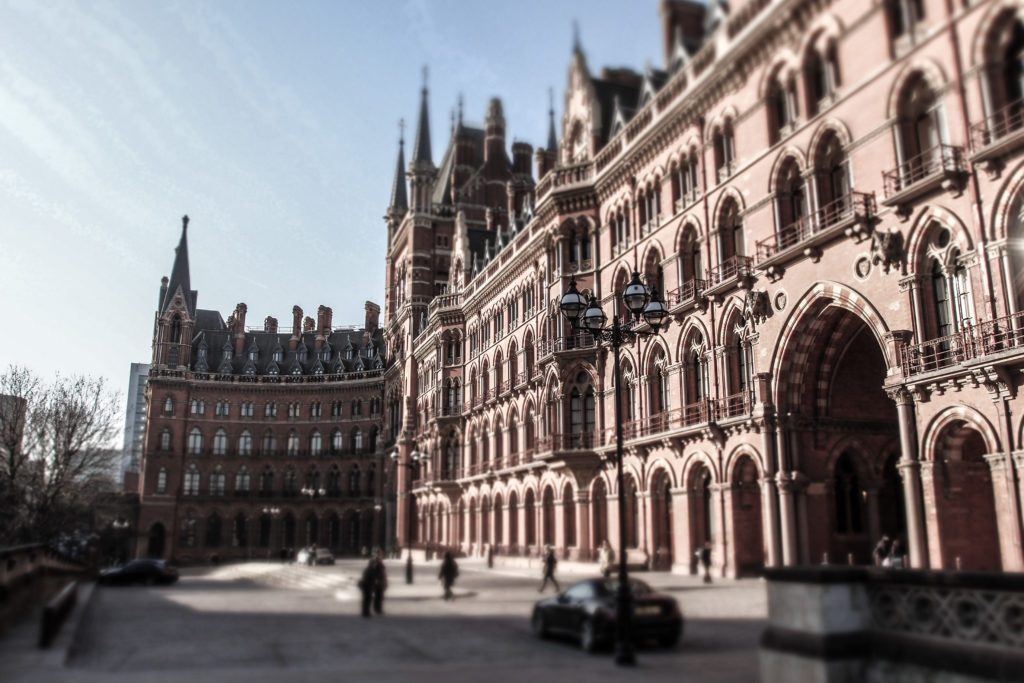

The famous Underground, ever expanding, has over 250 stations. One striking station is Westminster Station, designed by Michael Hopkins & Partners, where tough raw materials display engineering grandeur. Remarkable too are the over ground stations. These include the fantastical gothic St. Pancras Station, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and completed in 1876. It was recently remodelled extensively to incorporate the Eurostar service to Paris by Foster + Partners, and the futuristic latticed roof of the Kings Cross Station by John McAslan + Partners.

King’s Cross Western Concourse by Colin, 2012, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 Generic, from Wikimedia Commons

St Pancras hotel and station front by Graeme Maclean, 2012, is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0 Generic, from Flickr.com

London’s skyline is forever evolving and yet somehow preserves its identity through change. Even buildings that were once viewed as ‘eyesores’ are now beloved icons of the London skyline. The Battersea Power Station, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and completed in 1929, was originally opposed and protested against, yet more recently the public rallied to protect it. It has a similar story to its brother further down the Thames, what is now the Tate Modern, also designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, and redesigned in 2000 by Herzog & de Meuron. Many prominent buildings have several past lives and have been re-invented more than once. This may be the true reflection on London, where every street has historical layers with hints of the past history, but it is also alive, current, innovative and dynamic. London has no common theme to its architecture. It has not been developed according to a plan like Haussmann’s Paris. While this does not lead to harmonious and consistent architecture, it does represent the cultural diversity of London and its rich history. It has grown in an ad hoc way which is reflected in the jumble of historical buildings that make London so interesting and one of the world’s great cities, as the world is reflected in its fabric.